CASE REPORT | https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10002-1268 |

Pancreatic Mass: Remember Tuberculosis

1–5Department of Surgery, ESIC Medical College and PGIMSR and Hospital, New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author: Atul Jain, Department of Surgery, ESIC Medical College and PGIMSR and Hospital, New Delhi, India, Phone: +91 9999591415, e-mail: docatuljain@gmail.com

How to cite this article Jain A, Mishra NK, Nath P, et al. Pancreatic Mass: Remember Tuberculosis. World J Endoc Surg 2019;11(3):80–81.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Pancreatic tuberculosis is a rare disease. Patients with pancreatic tuberculosis often present with nonspecific symptoms, such as low-grade fever, weight loss, and abdominal pain, and with or without a history of tuberculosis or pancreatic disease. It can be misdiagnosed on account of low index of suspicion due to its rarity, and its presenting symptoms are shared by other common pancreatic conditions such as pancreatic malignancy. This could result in unnecessary surgery. As this is a treatable disease which does not require surgery, it is imperative to diagnose this condition preoperatively. We report this patient of pancreatic mass presenting as locally advanced pancreatic malignancy, subsequently diagnosed to be pancreatic tuberculosis and successfully managed with antitubercular medications.

Keywords: Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Pancreatic mass, Pancreatic tuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal tuberculosis is a common site for extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB). It is seen in 5–12% of patients with tuberculosis (with a high prevalence in endemic countries) and almost 11–16% of these patients with EPTB are found to have abdominal involvement.1 Despite this increasing trend, pancreatic involvement in tuberculosis remains uncommon. It was first reported by Auerbach.2 We present a case of pancreatic tuberculosis masquerading as pancreatic malignancy both on clinical presentation and on imaging studies. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was based on the fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) which showed granuloma with caseation necrosis with the presence of acid-fast bacilli.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 40-year-old thin built, malnourished male presented to surgery OPD with complaints of swelling in the upper abdomen, fever, on and off vomiting for 15 days. There was loss of appetite, irregular bowel habit, and loss of weight. On abdominal examination a single, nontender, firm, fixed intra-abdominal mass of size 4 × 4 cm was palpable in epigastric region. There were no other organomegaly and there was no evidence of free fluid. Laboratory examination showed a hemoglobin level of 8.5 g% and the rest of the parameters and tumor markers (CEA, CA19.9) were within normal limits.

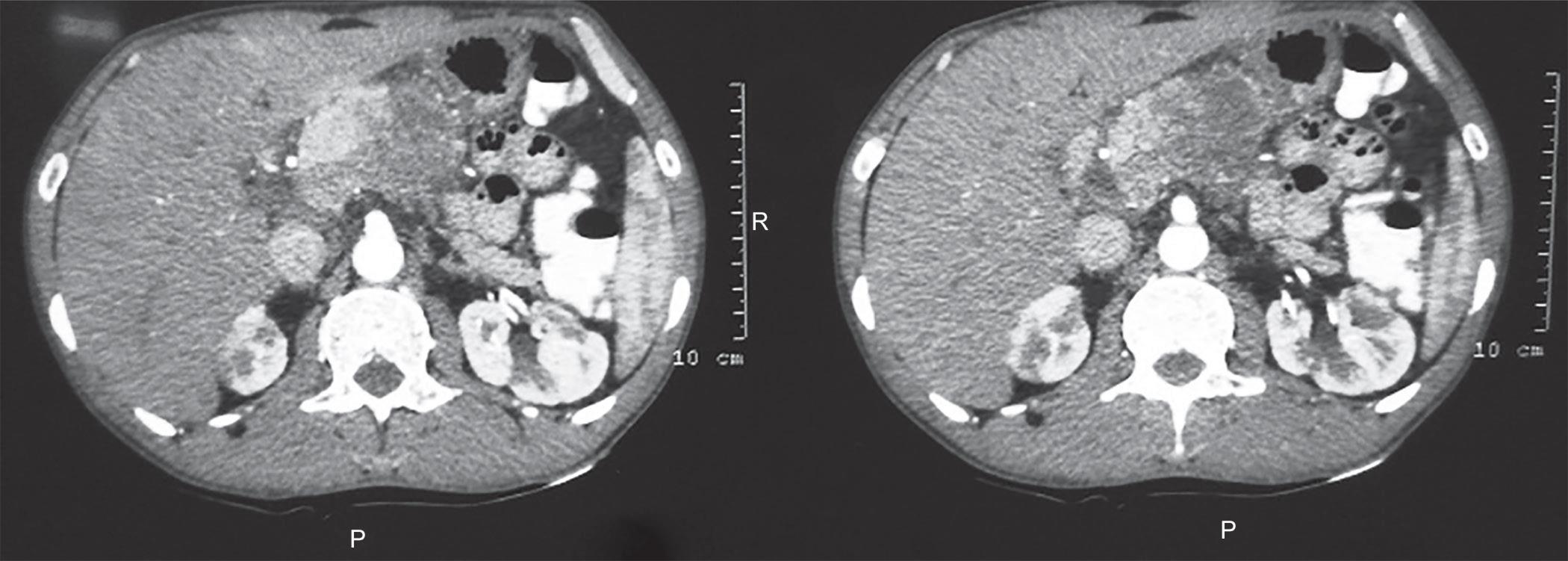

Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen showed a hypoechoic mass in the para-aortic region. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen was done, which revealed an ill-defined lesion predominantly hypodense along the inferior margin of the pancreatic body with loss of fat planes and involving a greater curvature of stomach and multiple heterogeneous lymph nodes in the peripancreatic, pre- and para-aortic region, likely mitotic in etiology (Fig. 1).

Clinical and radiological findings were suggestive of a locally advanced pancreatic malignancy and as it seemed unresectable, he was planned for chemotherapy and investigated accordingly. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) whole body and tissue biopsy were done for further management plan. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT showed a large lobulated FDG avid heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion in the body of pancreas and peripancreatic, mesenteric lymphnode were present, likely mitotic. Subsequent USG-guided FNAC of the pancreatic mass showed a caseous granulomatous necrosis with normal pancreatic tissue compatible for tuberculosis (Fig. 2). The diagnosis of pancreatic tuberculosis was thus reached based on these findings.

Standard antitubercular therapy (ATT) was started as per the RNTCP guideline, with an intensive phase for 2 months, and followed by the continuation phase of 4 months which was extended for a further 2 months. The lump regressed in size gradually and disappeared clinically completely after 5 months of therapy and radiologically after 6 months. The patient remains symptom free and healthy at the 6-month follow-up since completion of the ATT.

DISCUSSION

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is a diagnostic problem, especially when an unusual organ such as the pancreas is involved3 as it is biologically protected from infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, probably because of the presence of pancreatic enzymes. The possible way of infection is through hematogenous or spread from contagious pancreatic lymphnodes.4

The clinical presentation of pancreatic tuberculosis is often insidious, with nonspecific constitutional symptoms occurring frequently.5 According to the study by Saluja et al., the three most common complaints with which patients having pancreatic tuberculosis can present are abdominal pain, jaundice, and weight loss.6 Xia et al. in their study reported that the predominant symptoms were abdominal pain (75–100%), anorexia, weight loss (69%), malaise, weakness (64%), fever, and night sweats (50%).7 As seen in our case the patient presented with fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, and weakness which were nonspecific.

Fig. 1: Computed tomography image showing a large pancreatic mass with lymph nodes

Fig. 2: FNAC showing pancreatic tissue with caseating necrotic tissue

Ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) are often used as first-line diagnostic modalities when there is a suspicion of pancreatic pathology based on the presenting signs of patients.5 They can reveal both hypodense and hyperechoic lesions, usually found in the head of the pancreas. These solid or cystic lesions are, however, nonspecific, as pancreatic adenocarcinomas, cystadenocarcinomas, and pancreatic psuedocysts can show similar appearance frequently.6 Tuberculous lymph nodes are enlarged and can be conglomerated. On ultrasound examination, the enlarged lymph nodes contain a central hypoechoic area, whereas on enhanced CT they show central liquefied substance having low attenuation and peripheral inflammatory lymphatic tissue with higher attenuation.8 Therefore, to establish the diagnosis of pancreatic TB, histological, cytological, and bacteriological confirmations are necessary. Ultrasound-guided (USG) or CT-guided FNAC has been used to confirm the diagnosis and to prevent unnecessary laparotomies.7

In this case, the diagnosis was made by USG-guided FNAC. There are no specific guidelines for management because of the rarity of the disease. The patient in this case report responded well to the antitubercular chemotherapy.

CONCLUSION

Isolated pancreatic TB is extremely rare and may present as discrete pancreatic masses. Both clinical and radiographic presentation can mimic malignancy; clinicians should have a high suspicion of infectious processes such as TB as a potential etiology of such masses. Also, TB should be considered as a cause of any suspicious pancreatic lesion, especially in patients from areas where the infection is endemic. The majority of patients respond well to antitubercular chemotherapy and prognosis is good.

REFERENCES

1. Yokoyama T, Miyagawa S, Noike T, et al. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46(27):2011–2014.

2. Auerbach O. Acute generalized miliary tuberculosis. Am J Pathol 1944;20(1):121–136.

3. Hari S, Seith A, Srivastava DN, et al. Isolated tuberculosis of the pancreas diagnosed with needle aspiration: a case report and review of the literature. Trop Gastroenterol 2005;26(3):141–143.

4. Franco-Paredes C, Leonard M, Jurado R, et al. Tuberculosis of the pancreas: report of two cases and review of literature. Am J Med Sci 2002;323(1):54–58. DOI: 10.1097/00000441-200201000-00010.

5. Sharma SK, Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res 2004;120(4):316–353.

6. Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, et al. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic tuberculosis: a two decade experience. BMC Surg 2007;7:10. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2482-7-10.

7. Xia F, Poon RT, Wang SG, et al. Tuberculosis of pancreas and peripancreatic lymph nodes in immunocompetent patients: experience from China. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9(6):1361–1364. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i6.1361.

8. Pereira JM, Madureira AJ, Vieira A, et al. Abdominal tuberculosis: imaging features. Eur J Radiol 2005;55(2):173–180. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.04.015.

________________________

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.