CASE REPORT | https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10002-1408 |

Bilateral Pheochromocytoma: An Atypical Cause of Myocardial Infarction in a Young Male

1,2Department of Surgery, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

3,4Department of Pathology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

5RG Centre for Endocrinology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Corresponding Author: Bushra Siddiqui, Department of Pathology, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, Phone: +91 9897127431, e-mail: drbushrasiddiqui85@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Aim: To describe a rare case of bilateral pheochromocytoma in a young male presenting with two episodes of myocardial infarction.

Background: Pheochromocytoma is a catecholamine-producing tumor which arises from the adrenal medulla or rarely from an extra-adrenal site. It may present with a wide range of clinical symptoms and signs, ranging from headache, palpitations, and paroxysmal hypertension to rare events such as cardiomyopathy, cardiogenic shock, seizures, and intracranial bleeding.

Case description: We report a case of a 39-year-old male who presented to us with complaint of pain abdomen, palpitation, episodic headache, and shortness of breath for last 1 year. He also had history of two episodes of myocardial infarction during the last 9 months. After careful history, examination and investigations he was diagnosed as a case of bilateral functional adrenal pheochromocytoma with secondary cardiomyopathy. Bilateral open transperitoneal adrenalectomy was done and patient improved symptomatically. Histopathology of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of bilateral benign pheochromocytma. Owing to this rare presentation of a very rare tumor this case is being reported here.

Conclusion: Functional pheochromocytoma rarely presents with cardiomyopathy and myocardial infarction. There should be a high level of suspicion if a young patient presents with myocardial infarction in the normal coronary angiography.

Clinical significance: This case illustrates an uncommon presentation of pheochromocytoma presenting with two episodes of myocardial infarction in a young man with normal coronary angiography. A high suspicion index for pheochromocytoma is required in such cases.

How to cite this article: Faridi SH, Harris SH, Afrose R, et al. Bilateral Pheochromocytoma: An Atypical Cause of Myocardial Infarction in a Young Male. World J Endoc Surg 2021;13(2):64-67.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

Keywords: Bilateral adrenalectomy, Bilateral pheochromocytoma, Cardiomyopathy, Myocardial infarction

BACKGROUND

Pheochromocytoma is a catecholamine-secreting tumor that arises from chromaffin tissue of the sympathetic nervous system most commonly from adrenal medulla. It has been estimated to occur in 0.05-0.2% of patients with diastolic hypertension.1 The majority are benign and unilateral, characterized by the production of catecholamines and other neuropeptides. They are more frequent between the 3rd and 5th decades of life; however, 10-25% can be associated with genetic familial syndromes (Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, type 1 neurofibromatosis, and Von-Hippel-Landau disease) in younger ages. The manifestations of pheochromocytoma include paroxysms of severe headaches, diaphoresis, anxiety, tremulousness, chest and/or abdomen pain, nausea and vomiting, as well as generalized weakness and paroxysmal hypertension.1 Cardiac features of pheochromocytoma include different types of arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and congestive heart failure, as well as characteristics of acute coronary syndrome.2

Increased catecholamine levels can cause myocardial ischemia because of severe vasospasm and/or endothelial dysfunction.3 Exposure to increased catecholamine levels has also been shown to disrupt permeability of myocardial cells with secondary increases in intracellular calcium levels, which has a direct toxic effect on cardiomyocytes.4 We hereby report a case of a 39-year-old male who had bilateral functional pheochromocytoma with secondary cardiomyopathy with history of two episodes of myocardial infarction in the recent past. Bilateral adrenalectomy was done and all of his symptoms improved.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 39-year-old male patient presented to us with history of pain abdomen, palpitation, episodic headache, and shortness of breath associated with sweating for last 1 year. Further history revealed that pain in abdomen was initially mild to moderate in intensity localized to the right side of abdomen and later became generalized and became severe in intensity for last 3 months.

He also complained of episodes of anxiety and palpitations associated with sweating for last 1 year especially at night time, which used to wake him up during sleep.

There was also history of episodic headache which was generalized and associated with nausea and vomiting for last 3 months. Patient complained of progressively increasing shortness of breath for last 3 months. Initially he was able to do his routine activities, but for last 1 month he was completely bed ridden. There was no history of any addiction and there was nothing significant in the family history.

Patient was treated for anterior wall myocardial infarction 9 months back. His coronary angiography was normal as per the records and only thrombolysis was done. He also had history of 2nd episode of myocardial infarction (inferior wall) 3 months back for which again thrombolysis was done and his coronary angiography was normal. His abdominal complaints were not assessed at that time.

His physical examination at the time of admission revealed a blood pressure of 136/94 mm Hg, a regular pulse rate of 90 beats/minute. He was not tachypneic at rest. On per abdominal examination there was a firm, ballotable lump of size 10 x 10 cm present in the right flank. All other abdominal and systemic examination was unremarkable.

His ultrasonography of abdomen was suggestive of bilateral suprarenal masses. On the right side it was 11 × 9 cm and on left side it was 5 × 3 cm. He was advised 24-hour urinary Vanillylmandelic Acid (VMA) which was found to be highly elevated, that is, 331 mg/24-hour (Normal value- 1.60-7.30 mg/24 hours). All his other hematological investigations were within normal limits. His electrocardiography was suggestive of old changes of myocardial infarction (Q waves in lead V1- V3 and Lead II and III). His echocardiography showed severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction with dilated cardiomyopathy and ejection fraction of only 35%.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of abdomen was advised and it was suggestive of well defined, smooth walled soft tissue density lesion involving bilateral adrenal gland. Size of the right adrenal lesion was 11.4 × 9.7 × 9.3 cm and on the left side it was 4.6 × 4.5 × 4.1 cm (Fig. 1).

Figs 1A and B: Coronal (A) and transverse (B) section CT scan abdomen showing bilateral pheochromocytoma (White arrows)

On the basis of history, examination, and investigations we made the diagnosis of bilateral functional adrenal pheochromocytoma with secondary cardiomyopathy.

During the admission patient had episodes of hypertension with anxiety and sweating. He was started on oral prazosin 1 mg once daily for α blockade and the dose was gradually increased to 2 mg daily when the patient started complaining of postural hypotension and nasal stuffiness and on examination there was tachycardia. After that β blocker metoprolol 50 mg once daily was started to control tachycardia.

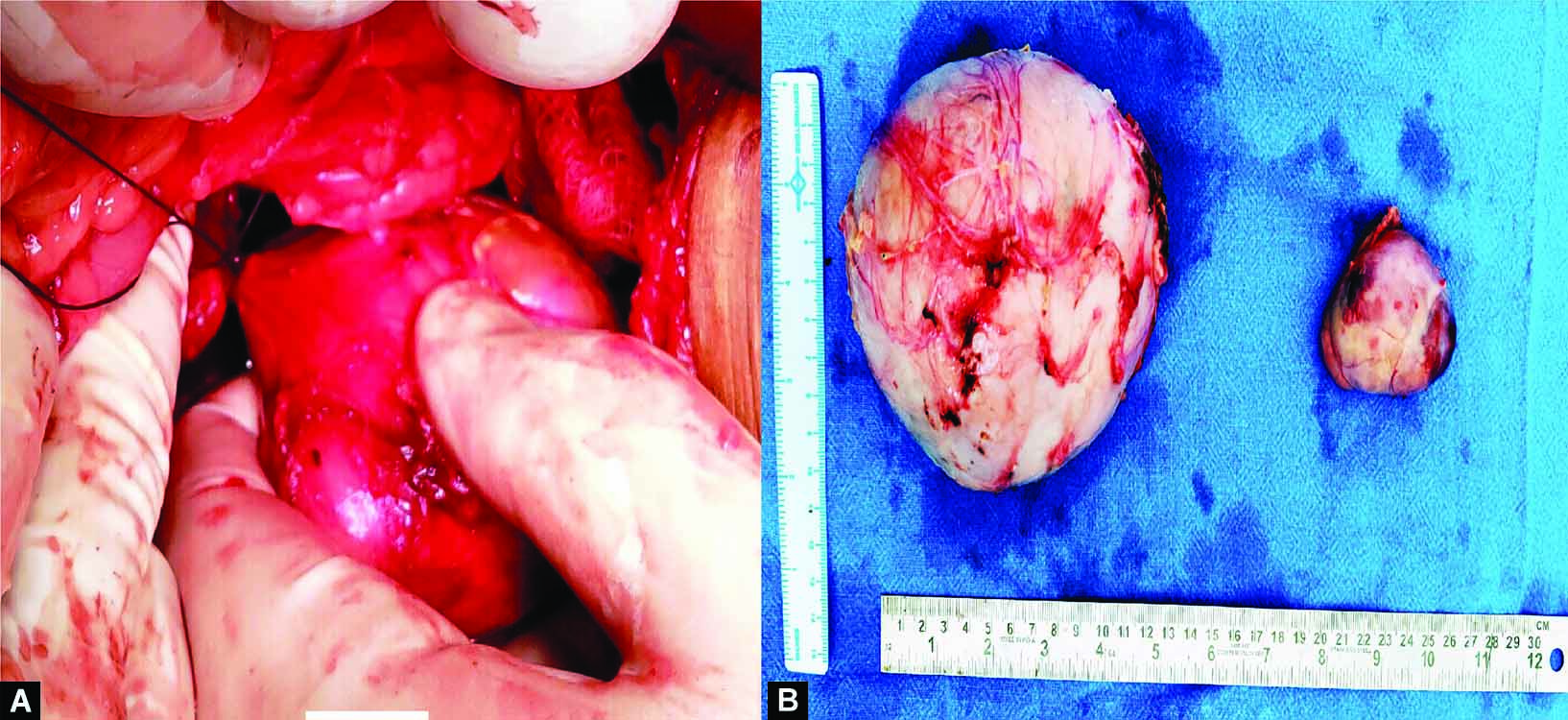

We planned the patient for open bilateral transperitoneal adrenalectomy. Vertical midline laparotomy was done and hepatic flexure of colon was mobilized. There was a large right adrenal mass in close relation to inferior vena cava displacing the right kidney (Fig. 2). During the mobilization of tumor the patient developed hypertension (220/120 mm Hg) for which intravenous nitoglycerine was started @ 20 mcg/minute. After the removal of right adrenal gland, left side adrenalectomy was also done. Soon after bilateral adrenalectomy patient developed severe hypotension and his blood pressure dropped to 60/46 mm Hg. Hypotension was managed with noradrenaline @ 0.2 mcg/kg/minute and adrenaline @ 0.5 mcg/kg/minute. Both noradrenaline and adrenaline were continued postoperatively and gradually tapered over a 4 hours period when the patient was able to maintain his blood pressure

Figs 2A and B: (A) Peroperative photograph showing large right adrenal mass (white arrow) overlying the right kidney; (B) Photograph after right adrenalectomy showing inferior vena cava (white arrow) and the right kidney

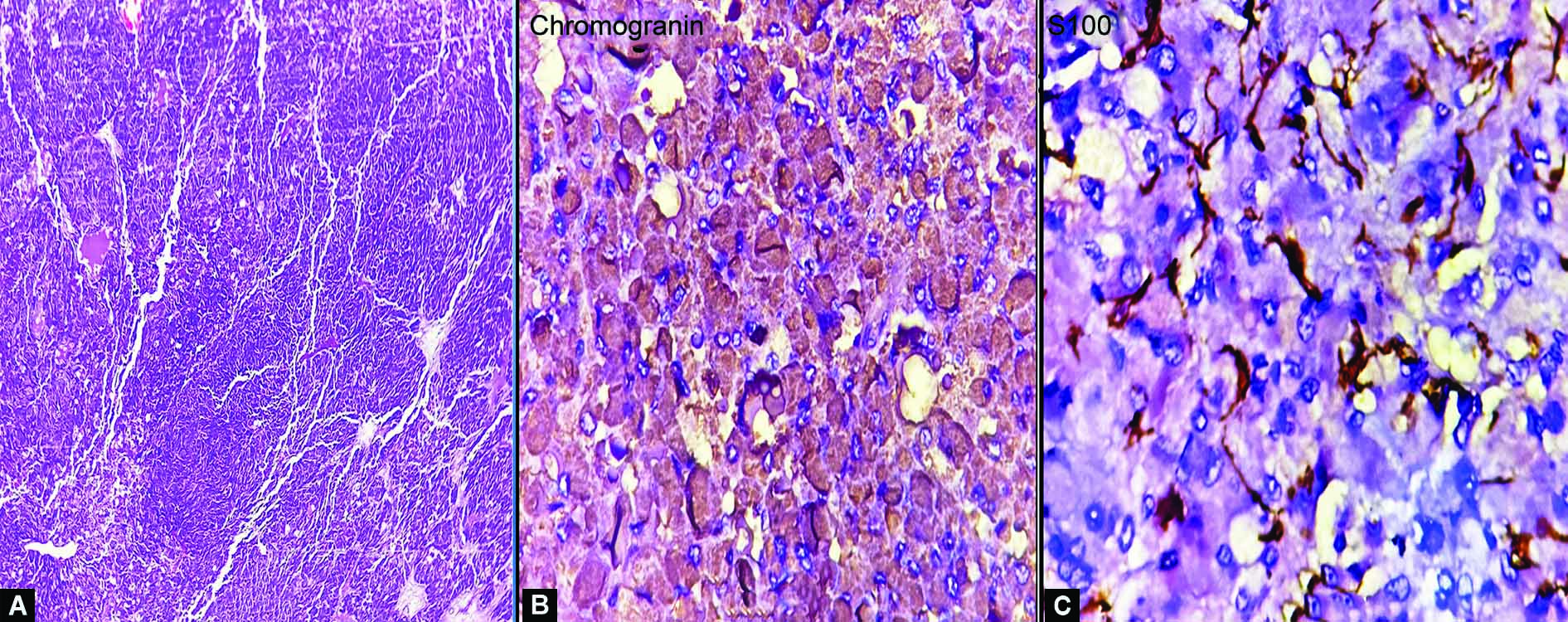

Right side tumor measured 13 × 11 cm and on the left side tumor measured 7 × 5 cm (Fig. 3). Histopathological examination of the tumors confirmed the diagnosis of bilateral pheochromocytoma of adrenal gland without capsular or vascular invasion (Fig. 4). Pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scoring scale (PASS Score) was 7 suggesting aggressive nature of the tumor.

Figs 3A and B: (A) Peroperative photograph of left adrenalectomy; (B) Photograph of the excised right and left adrenal mass specimens

Figs 4A and C: (A) H&E x 100: Section showing round to ovoid cells with granular cytoplasm and nuclei showing hyperchromasia with moderate to marked pleomorphism arranged in sheets, trabeculae and alveolar pattern; (B) The cells show cytoplasmic positivity for chromogranin; (C) Sustentacular cells show positivity for S100

Postoperatively patient made an uneventful recovery and his symptoms improved. He was advised prednisolone 5 mg and fludrocortisones 0.1 mg once daily lifelong to prevent adrenal insufficiency. Postoperatively urinary VMA was normal.

DISCUSSION

Pheochromocytoma is a real diagnostic challenge for clinicians because of the rarity and variability of clinical presentation. About 90% of these tumors arise from the adrenal gland and 90% of them are benign.5 It produce typical systemic manifestations by catecholamine secretion, most frequently norepinephrine followed by epinephrine and dopamine. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas constitute 10% of the tumors and are more likely to be malignant (30%).5 Because a remarkable number of patients still die from overproduction of hormones, the main goals of treatment are tumor mass control and hormonal symptoms even if the tumor is malignant or disease is metastatic.6

Cardiac manifestations of pheochromocytoma include hypertension, myocardial hypertrophy, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary edema, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, and rarely myocardial infarction.7,8 Our patient had history of two episodes of myocardial infarction during the last 9 months and his left ventricular ejection fraction was only 35%. He was also having severe dyspnea on mild exertion.

Most common cardiovascular manifestation of pheochromocytoma is hypertension which is seen in >70% of the patients. Pheochromocytoma is regarded as a surgically treatable cause of hypertension. So it must be taken into consideration with hypertension (paroxysmal or persistent) in each patient presenting with an adrenal tumor. Hypertension is paroxysmal in only 50% of cases, and persists in the rest, making diagnosis difficult.9 Our patient had paroxysmal hypertension associated with sweating, headache, and anxiety.

There are only very few case reports of pheochromocytoma associated with acute myocardial infarction. The majority of these cases have normal coronary arteries.2,7 The process of myocardial infarction or segmental myocardial dysfunction associated with pheochromocytoma was linked to coronary spasm or catecholamine-induced legitimate toxic effect.3,10 Catecholamines upturn left ventricular effort by inducing left ventricular hypertrophy from hypertension and rise in heart rate. Variations in the coronary arteries comprise stiffening of media hypothetically impairing blood flow to myocardium and coronary vasospasm.11 Catecholamines can lead to cardiac myocyte apoptosis.12 Continued vasospasm can cause endothelial injury and stimulate platelet aggregation. In our case patient had two episodes of myocardial infarction but his coronary angiography was normal each time. During both of these episodes only thrombolysis was done and his condition improved.

The only potentially curative approach in a patient with pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. Prior to surgery, in the case of a hormonally active disease, adequate alpha-adrenergic blockade is mandatory.13,14 This prevents intraoperative complications related to massive catecholamine release, such as a hypertensive crisis, arrhythmias, and myocardial infarction. In general, the patients who suffer from acute myocardial infarction are treated with β blockers. But, in patients with pheochromocytoma, administration of β blockers will cause paradoxical hypertension due to unopposed α-adrenergic receptor stimulation, therefore β blockers are prescribed once there is adequate α-adrenergic blockade.2 In our case, patient was initially prescribed α-adrenergic blocker Prazosin 1 mg daily and later the dose was increased to 2 mg and later on β blockade was done with Metoprolol 50 mg once daily.

As there is difference in the anatomy of the right and left adrenal glands, surgical approaches are different for right and left side adrenalectomy. Right adrenalectomy is believed to be more difficult due to its proximity to the inferior vena cava and duodenum and the shorter vein which directly drains in to the inferior vena cava.15 In our case, there were bilateral tumors and the right side tumor was larger than the left side. Removal of the right gland was technically more challenging then the left side.

CONCLUSION

This case illustrates an uncommon presentation of pheochromocytoma presenting with two episodes of myocardial infarction in a young man with normal coronary angiography. A high suspicion index for pheochromocytoma is required in such cases because it is a lethal, but potentially curable disease. Since the treatment data is so scarce, case reports are a valuable source of clinicians’ knowledge. Surgery can play a significant role in extending the survival of patients.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

This case illustrates an uncommon presentation of pheochromocytoma presenting with two episodes of myocardial infarction in a young man with normal coronary angiography. A high suspicion index for pheochromocytoma is required in such cases.

REFERENCES

1. Manger WM. An overview of pheochromocytoma: history, current concepts, vagaries, and diagnostic challenges. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1073:1-20. DOI: 10.1196/annals.1353.001

2. van Oordt CWMHTwickler TBvan Asperdt FGMHet al. Pheochromocytoma mimicking an acute myocardial infarction Neth Heart J 2007;15(7-8):248-251. DOI: 10.1007/BF03085991

3. Beedupalli JAkkus NI. Concealed pheochromocytoma presenting as recurrent acute coronary syndrome with STEMI: case report of a patient with hyperthyroidism. Herz 2014;39(04):476-480. DOI: 10.1007/s00059-013-3826-y

4. Bloom S. Catecholamine cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1987;317(14):900-901. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM198710013171413

5. O’Connor DT. The adrenal medulla, catecholamines, and phaeochromocytoma. In: Cecil RL, Goldman L, Ausiello DA, editors. Cecil’s Textbook of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003.1419-1424.

6. Ajallé RPlouin PFPacak K et al. Treatment of malignant pheochromocytoma. Horm Metab Res 2009;41(09):687-696. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1231025

7. Lenders JWMEisenhofer GMannelli M,et al. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 2005;366(9486):665-675. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5

8. Schurmeyer THEngeroff BDralle H,et al. Cardiological effects of catecholamine-secreting tumours. Eur J Clin Invest 1997;27(03):189-195. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1997.850646.x

9. Werbel SSOber KP. Pheochromocytoma: update on diagnosis, localization and management. Med Clin North Am 1995;79(01):131-153. DOI: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30088-8

10. Nanda ASFeldman ALiang CS. Acute reversal of pheochromocytoma-induced catecholamine cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 1995;18(07):421-423. DOI: 10.1002/clc.4960180712

11. Irwin Klein. Endocrine disorders and cardiovascular disease. In:, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, Braunwald Eeds. Braunwald’s Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 9th ed. Elsevier Saunders Company 2012;1829-1843.

12. Communal CSingh KPimentel DRet al. Norepinephrine stimulates apoptosis in adult rat ventricular myocytes by activation of the _beta -adrenergic pathway Circulation 1998;98(13):1329-1334. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.98.13.1329

13. Babinska APeksa RSworczak K. Primary malignant lymphoma combined with clinically “silent” pheochromocytoma in the same adrenal gland. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:289. DOI: 10.1186/s12957-015-0711-6, indexed in PubMed: 26419235.

14. Januszewicz WPrejbisz AJanuszewicz A, et al. Pheochromocytoma— disease that can stimulate many different syndromes Nadciśnienie Tętnicze 2002;6(03):217-228.

15. Gimm ODuh QY. Training in adrenal surgery faces many but solvable challenges. Gland Surg 2019;8(Suppl 1):S3-S9. DOI: 10.21037/gs.2019.01.08

________________________

© The Author(s). 2021 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.