ORIGINAL ARTICLE |

https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10002-1427 |

Standardized Stepwise Technique for Thyroidectomy: Patient Outcomes from a Single Center in Uzbekistan

Department of Endocrine Surgery, The Center for the Scientific and Clinical Research of Endocrinology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Corresponding Author: Murodjon Rashitov, Department of Endocrine Surgery, The Center for the Scientific and Clinical Research of Endocrinology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, Phone: +998946400131, e-mail: murodrashitov@gmail.com

Received on: 01 October 2019; Accepted on: 20 July 2022; Published on: 15 April 2023

ABSTRACT

Background: Thyroid operations are performed by general surgeons, otolaryngologists, endocrine surgeons, and surgical oncologists. While thyroidectomy techniques are well described, differences persist among surgeons. A stepwise approach to thyroidectomy may promote standards of care and improve outcomes and training.

Methods: A total of 177 patients underwent thyroid operations in The Center for the Scientific and Clinical Research of Endocrinology, Department of Endocrine Surgery of Uzbekistan, during 2017–2018, with a stepwise technique for thyroidectomy. The series included 155 women and 12 men, with a mean age of 41.4 ± 12.8 years. Evaluations included thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free T4 levels, fine needle aspiration cytology, ultrasonography of the thyroid gland, cervical lymph nodes and adjacent structures, and vocal cord assessment. We designated five steps of thyroidectomy: (1) Medial mobilization of the gland and division of the middle thyroid vein; (2) Dissection of the anterior suspensory ligament between the superomedial lobe and cricoid/thyroid cartilage, with the division of the superior pole vessel branches, (3) Division of the branches of the inferior thyroid artery (ITA) with preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and both parathyroid glands (PTGs); (4) Division of the posterior suspensory ligament (of Berry) that connects the lobe to the cricoid cartilage and first and second tracheal rings; and (5) Central and/or lateral lymph node dissection, if indicated.

Results: A total of 134 patients (75.7%) had nodular goiter, 29 had Graves’ disease (GD) (16.4%), and 14 had thyroid carcinoma (7.9%). A total of 107 patients (60.5%) were euthyroid, 37 (20.9%) had controlled hyperthyroidism, and 33 (18.6%) had already been treated for hypothyroidism before surgery. Operations included total or near-total thyroidectomy (98, 55.4%), lobectomy (60, 33.9%), or lesser resections (19, 10.7%). There were two (1.1%) temporary and no permanent RLN palsies. Temporary hypoparathyroidism (lasting <11 days) occurred in 37 (20.9%) patients, but no patients suffered permanent hypoparathyroidism.

Conclusion: Comprehension of thyroid anatomy and systematization of technical steps may improve outcomes and enhance training in thyroid surgery.

How to cite this article: Rashitov M. Standardized Stepwise Technique for Thyroidectomy: Patient Outcomes from a Single Center in Uzbekistan. World J Endoc Surg 2022;14(2):37-41.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

Keywords: Optimization, Thyroid surgery, Thyroidectomy.

INTRODUCTION

The selection of surgical technique is based on the characteristics of the disease and the experience and preferences of the surgeon. The thyroidectomy technique has been well described elsewhere for centuries.1-8 At present, thyroid operations are performed by general surgeons, otolaryngologists, endocrine surgeons, and surgical oncologists.9-20 Many helpful maneuvers and techniques have been proposed. While thyroidectomy techniques are well described, differences persist among surgeons. The development of a standardized, highly effective, safe, detailed algorithm for surgical intervention is key to a successful surgery with a low risk of complications.

However, to date, no generally accepted algorithm with identified surgical “steps” for operations on the thyroid gland exists. Most specialists describe only the general principles of thyroidectomy, which, from a clinical and educational perspective, are often not sufficiently informative. A stepwise approach to thyroidectomy may promote standards of care and improve outcomes and training.

Based on the available literature and our clinical material, by systematizing existing techniques, we identified five steps for the thyroidectomy technique based on the mobilization and sequential section of connective tissue structures fixed to the thyroid gland. A systematic stepwise approach to the thyroidectomy technique may facilitate a better understanding of the topographic–anatomical features of the thyroid gland and can serve as a standard care.

Purpose: To describe the outcomes for a prospective series of patients who underwent thyroidectomy via a standardized approach based upon the sequential division of the soft tissues surrounding the gland.

MATERIALS AND RESEARCH METHODS

A total of 177 patients underwent thyroid operations by four surgeons in Uzbekistan during 2017–2018. The series included 155 women and 12 men, with a mean age of 41.4 ± 12.8 years. Evaluations included TSH and free T4 levels, fine needle aspiration cytology, ultrasonography of the thyroid gland, cervical lymph nodes and adjacent structures, and vocal cord assessment (before and after surgery).

All surgeons have been operating on thyroid and parathyroid pathologies for more than 20 years. In our department, we perform more than 700 surgical operations on the thyroid and 30 surgical operations on the PTGs each year.

We designated five steps for the thyroidectomy: (1) Medial mobilization of the gland and division of the middle thyroid vein; (2) Dissection of the anterior suspensory ligament between the superomedial lobe and cricoid/thyroid cartilage, with the division of superior pole vessel branches; (3) Division of the branches of the ITA with preservation of the RLN and both PTGs; (4) Division of the posterior suspensory ligament (of Berry) that connects the lobe to the cricoid cartilage and first and second tracheal rings; and (5) Central and/or lateral lymph node dissection, if indicated.

The frequency of postoperative complications, such as hypocalcemia and RLN palsy (temporary or permanent), and postoperative bleeding were analyzed. Complications were studied as functions of sex, age, preoperative diagnosis, thyroid status, the purpose of the operation (primary, recurrent, and completion), and the extent of the operation.

The RLN was routinely identified in all patients and carefully traced to the entrance of the larynx. All PTGs were identified, if possible. In the event of impaired blood supply, the PTG was minced with a scalpel and transplanted into the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 41.4 ± 12.8 years, and women were more prevalent than men (155 and 12, respectively) (Table 1). The study showed that the majority of patients had a diagnosis of multinodular goiter (75.7%), 16.4% had GD, and 7.9% had thyroid cancer. A total of 60.5% patients were euthyroid. Thirty-three (18.6%) had already been treated for hypothyroidism. Patients with thyrotoxicosis, including patients with GD and multinodular toxic goiter, were prepared for surgery with oral methylazole 30 mg/day until compensation was achieved and then administered Lugol’s solution for approximately 2 weeks.

| Demographic data | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 177 | 100 |

| Age (year) | 41.4 ± 12.8 | |

| Sex (W/M) | 155/12 | 88/12 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | ||

| Multinodular goiter | 134 | 75.7 |

| GD | 29 | 16.4 |

| Thyroid cancer | 14 | 7.9 |

| Thyroid gland/tumor measures | ||

| Multinodular goiter (mean specimen weight) | 84 ± 62 gm | |

| GD (mean specimen weight) | 55 ± 28 gm | |

| Thyroid cancer (tumor size) | 2.5 ± 0.73 sm | |

| Thyroid status | ||

| Euthyroid | 107 | 60.5 |

| Hyperthyroid | 37 | 20.9 |

| Hypothyroid | 33 | 18.6 |

| Purpose of operation | ||

| Primary | 175 | 98.9 |

| Recurrence | 1 | 0.6 |

| Completion | 1 | 0.6 |

| Number of operations | ||

| Total thyroidectomy | 80 | 45.2 |

| Near total thyroidectomy | 18 | 10.2 |

| Hemithyroidectomy | 60 | 33.9 |

| Less than hemithyroidectomy | 19 | 10.7 |

| Postoperative diagnosis | ||

| Benign | 162 | 91.5 |

| Malignant | 15 | 8.5 |

| Complications of operations | ||

| Temporary RLN palsy | 2 | 1.1 |

| Permanent RLN palsy | 0 | 0.0 |

| Temporary hypoparathyroidism | 37 | 20.9 |

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 0 | 0.0 |

| Postoperative (PO) bleeding | 1 | 0.6 |

The aim of the operation was primary surgery for 175 patients, recurrence for one patient, and completion surgery for papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) for one patient. An analysis of the number of operations showed that 45.2% were total thyroidectomies, 10.2% were near total thyroidectomies, 33.9% were hemithyroidectomy, and 10.7% were less than hemithyroidectomies.

The frequency of complications after surgery was analyzed. Postoperative intermediate-density lipoprotein showed that temporary RLN palsy was identified in two patients (1.1%), and no permanent RLN palsy was observed. We do not routinely identify the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve during thyroid operations. Temporary hypocalcemia was observed in 37 patients (20.9%), lasting approximately 11 days after administration of calcium and vitamin D tablets. Postoperative bleeding was observed in one patient, which required re-exploration. The removed specimens were weighed: the mean weight of multinodular goiter specimens was 84 ± 62 gm, and the mean weight of GD specimens was 55 ± 28 gm. In our series, no tracheomalacia was encountered.

Fifteen patients had PTC. Among them, 14 patients were preoperatively diagnosed with PTC (Table 2). Among them, seven patients had local lymph node metastases revealed by ultrasonography and confirmed intraoperatively; in addition to total thyroidectomy, therapeutic neck lymph node dissection of the central (VI level) and lateral compartments (II, III, and IV levels) was performed. Seven patients without evidence of local lymph node metastases underwent total thyroidectomy. All PTC patients were treated with radioactive iodine after total thyroidectomy. Tumor size between patients with lymph node metastases and those without did not differ between the two groups. Tumor size in the general group with PTC was 2.5 ± 0.73 sm. No distant metastases or extrathyroidal extensions were revealed in our series. One patient underwent surgery for nodular goiter and was found to have PTC on final histology. This patient underwent completion thyroidectomy after 1 month.

| TNM | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | ||

| T1a | 0 | 0 |

| T1b | 4 | 26.7 |

| T2 | 10 | 66.7 |

| T3 | ||

| T3a | 1 | 6.7 |

| T3b | 0 | 0 |

| T4 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 8 | 53.3 |

| N1a | 3 | 20 |

| N1b | 4 | 26.7 |

| M0 | 15 | 100 |

| M1 | 0 | 0 |

There were 29 (16.4%) patients with GD who were treated with total thyroidectomy after the course of treatment with antithyroid drugs (methimazole) was completed. The daily dose of methimazole was 30 mg/day. All patients with GD were administered Lugol’s solution at a dose of 5 gtt three times a day × 15 days preoperatively.

Analyses of complications of the operations showed that there were two (1.1%) temporary and no permanent RLN palsies. Temporary hypoparathyroidism (lasting <11 days) occurred in 37 (20.9%) patients, but no patients suffered permanent hypoparathyroidism. One (0.6%) postoperative hematoma required re-exploration. The types of surgical complications did not significantly differ between patients with multinodular goiter, GD, and PTC, although the tendency of temporary hypoparathyroidism was higher in patients with GD because of the chronic inflammatory nature of the disease.

We used the generally accepted thyroidectomy technique with the identification of the RLN and PTGs in our series. Furthermore, on the basis of this technique, we designated five steps for thyroidectomy:

-

Step one: Starting from the skin incision, continuing to the medial mobilization of the gland and finishing by division of the middle thyroid vein, if present, allows mobilization of the thyroid lobe up and medially, releasing the entire lateral surface (Fig. 1).

-

Step two: Dissection of the anterior suspensory ligament between the superomedial lobe and cricoid/thyroid cartilages, with division of superior pole vessel branches. At this stage, the thyroid lobe is retracted laterally and downwards for better visualization of avascular space or Reeve’s space between the thyroid lobe and thyroid cartilage. The endpoint of this step is the superior parathyroid gland (SPG), which is not mobilized in this step (Fig. 2).

-

Step three: Division of the branches of the ITA with preservation of the RLN and both PTGs. In the third step, the thyroid lobe, with the freed upper pole, is retracted upwards and medially, creating some tension in the lateral surface of the lobe. This makes it easy to identify the ITA. Identification of the ITA is key to identifying the RLN and inferior parathyroid gland (IPG). As these structures are mobilized and brought down by meticulous capsular dissection, the thyroid lobe becomes quite mobile. The vascular pedicle of the SPG and IPG are preserved. When this is impossible, the pedicle is removed, minced, and transplanted into the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Identification of the RLN can be safely performed in the tracheoesophageal groove in the supraclavicular area; then, we trace the RLN all the way to the entrance to the larynx. The ITA branches intersect as close as possible to the thyroid tissue. This allows preservation of the branches of the ITA supplying the SPG and IPG. The SPG is mobilized down with the surrounding fatty tissue at the time of mobilization of Zuckerkandl’s tubercle (Fig. 3).

-

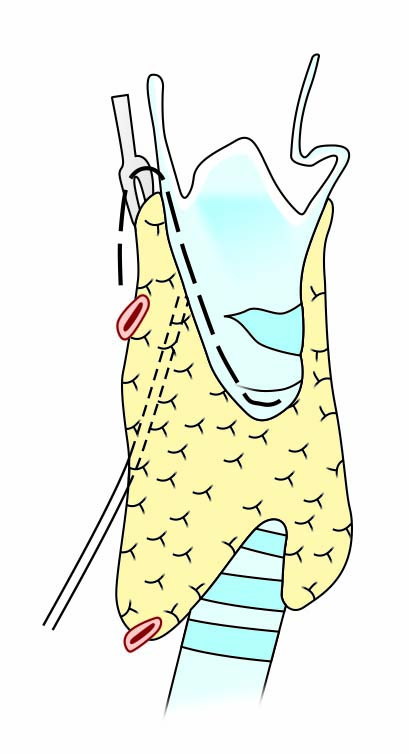

Step four: Division of the posterior suspensory ligament (of Berry) that connects the lobe to the cricoid cartilage and first and second tracheal rings. After careful inspection and ligation of the vessels, the posterior suspensory ligament (the Berry ligament) is dissected under the eye control of the RLN. This releases an almost completely mobilized thyroid lobe. Lobectomy is then performed; the contralateral lobe is removed in an identical manner if necessary (Fig. 4).

-

Step five: Central and/or lateral lymph node dissection, if indicated (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1: Step one of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy

Fig. 2: Step two of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy

Fig. 3: Step three of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy

Fig. 4: Step four of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy

Fig. 5: Step five of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy

DISCUSSION

As in any surgical procedure, surgical treatment of thyroid disease requires a highly experienced surgeon, who with personal experience and techniques can perform safe and effective operations. While there are different approaches for thyroidectomy, the majority of surgeons follow a well-known path, that is, identification of the main blood vessels, PTGs, and RLN during mobilization of the thyroid gland.

In our study, we systematized a stepwise approach to the generally accepted algorithm of thyroidectomy, which is utilized in many centers worldwide. The outcome of this technique is very favorable, with a low rate of complications.

Analyzing the obtained data, we note that transitory hypocalcemia was observed in 20.9% of patients because of the mobilization of the PTG due to temporary edema of the vascular pedicle of the gland. We attempted not to mobilize the SPG, which is higher and dorsal to the RLN, but left it in the fat pad where it is usually located. During the dissection of the RLN and the Berry ligament, the SPG was left almost untouched. Ligation of the ITA branches close to the thyroid tissue allowed the preservation of those supplying the SPG and IPG. The identification of the RLN throughout its length allowed its safe preservation to conduct a virtually bloodless operation and to predict the risks and consequences during the operation. Capsular dissection of the vessels and maintaining distance from the RLN in patients with chronic inflammatory thyroid diseases may prevent iatrogenic RLN palsy.

When analyzing the frequency of complications in correlation with other indicators, such as preoperative diagnosis, thyroid size, thyroid status, volume of operation, and other indicators, there was no significant difference. This again shows that the proposed tactic is highly effective and safe.

Thus, the designated five-step technique for thyroidectomy is a systematization of the present well-utilized surgical procedure based on a stepwise approach. In our understanding, a stepwise approach to thyroidectomy may promote standards of care and improve outcomes and training.

CONCLUSION

Comprehension of thyroid anatomy and systematization of technical steps may improve outcomes and enhance training in thyroid surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my teachers and those outstanding persons from whom I learned endocrinology and endocrine surgery. This paper is written using the knowledge I have gained from them and the inspiration from their work and life. They are Professor Said Ismailov (Uzbekistan), Professor Charles Proye (France), Professor Bruno Niederle (Austria), Professor Takahiro Okamoto (Japan), Professor David McAneny, Professor Pieter Noordzij, Professor Elizabeth Pearce, Professor Alan Farwell, Professor Stephanie Lee, Professor Gerard Doherty, Professor Gregory Randolph, Dr Frederick Drake (USA), and others.

Schematic illustrations of steps of the standardized stepwise technique for thyroidectomy are given in Figures 1 to 5.

REFERENCES

1. Halsted WS. The operative history of goiter. The author’s operation. Hosp Rep 1920;74(10):693–694. DOI: 10.1001/jama.1920.02620100053037

2. Becker WF. Presidential address: pioneers in thyroid surgery. Ann Surg 1977;185(5):493–504. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-197705000-00001

3. Kocher T. Uber Kropfextirpation und ihre Folgen. Arch Klin Chir 1883;29:254–337.

4. Crile GW. The Thyroid Gland. WB Saunders Philadelphia; 1923.

5. Lahey FH. Routine dissection and demonstration of recurrent laryngeal nerve in subtotal thyroidectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1938;66:775–777.

6. Mayo CH. Ligation and partial thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism. In: Mellish MH, editor. Collected Papers by the Staff of St. Mary’s Hospital, Mayo Clinic. Rochester: Mayo Clinic; 1910.

7. Gagner M. Endoscopic subtotal parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Br J Surg 1996;83(6):875. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800830656

8. Ikeda Y, Takami H, Sasaki Y, et al. Are there significant benefits of minimally invasive endoscopic thyroidectomy? World J Surg 2004;28(11):1075–1078. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-004-7655-2

9. Ismailov SI, Alimjanov NA, Babakhanov BK, et al. Long-term results after total thyroidectomy in patients with Grave’s disease in Uzbekistan: retrospective study. World J Endocr Surg 2011;3(2):79–82. DOI: 10.5005/jp-journals-10002-1062

10. Harness JK, Heerden JAV, Lennquist S, et al. Future of thyroid surgery and training surgeons to meet the expectations of 2000 and beyond. World J Surg 2000;24(8):976–982. DOI: 10.1007/s002680010168

11. Takami H, Ito Y, Okamoto T, et al. Revisiting the guidelines issued by the Japanese society of thyroid surgeons and Japan association of endocrine surgeons: a gradual move towards consensus between Japanese and western practice in the management of thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg 2014;38(8):2002–2010. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-014-2498-y

12. Dralle H, Musholt TJ, Schabram J, et al. German association of endocrine surgeons practice guideline for the surgical management of malignant thyroid tumors. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013;398(3):347–375. DOI: 10.1007/s00423-013-1057-6

13. Gardner IH, Doherty GM, McAneny D. Intraoperative nerve monitoring during thyroid surgery. Curr Opin in Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016;23(5):394–399. DOI: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000283

14. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016;26(1):1–133. DOI: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020

15. In H, Pearce EN, Wong AK, et al. Treatment options for Graves disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Am Coll Surg 2009;209(2):170–179. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.03.025

16. Patel KN, Yip L, Lubitz CC, et al. The American association of endocrine surgeons guidelines for the definitive surgical management of thyroid disease in adults. Ann Surg 2020;271(3):e21–e93. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003580

17. Randolph GW. Surgery of the Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020.

18. Sulibhavi A, Rubin SJ, Park J, et al. Preventative and management strategies of hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy among surgeons: an international survey study. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;41(3):102394. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102394

19. Kluijfhout WP, Pasternak JD, Drake FT, et al. Application of the new American thyroid association guidelines leads to a substantial rate of completion total thyroidectomy to enable adjuvant radioactive iodine. Surgery 2017;161(1):127–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.056

20. Passler C, Avanessian R, Kaczirek K, et al. Thyroid surgery in the geriatric patient. Arch Surg 2002;137(11):1243–1248. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.137.11.1243

________________________

© The Author(s). 2022 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.